Concerns mount over increased police usage of license plate readers.

Baltimore, MD - Specially assigned police officers have License Plate Readers (LPR's) mounted on their cars.

“Looks like one of our guys got a hit,” said Det. Brian Ralph, Baltimore Police.

Detective Brian Ralph can scan up to 3,000 tag numbers a shift, searching for stolen vehicles and violent criminals.

“So if someone is looking for a particular vehicle in reference to a robbery or murder or something like that, we can put that tag number into the system and it will hit if the vehicle happens to drive by,” said Hartman, Regional Auto Theft Task Force.

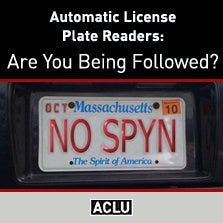

More than 320 LPRs are in use across Maryland. Information about every scanned license plate–even non-criminal–is stored at the Maryland Coordination and Analysis Center. That concerns the ACLU.

“As the data increases over time you get a more detailed picture of Marylanders’ movements. And that is information the government has no business knowing, absent some particular law enforcement need,” said David Rocah, ACLU.

But police say storing information could help in future cases, and the LPRs are way more effective than the naked eye.

“It’s really hard to see the tags for what we do every day and this LPR doesn’t miss a thing,” said Ralph.

It tracks the moves of tens of thousands of Marylanders every single day.

Police are trying to get funding for more plate readers, but the debate over storing the information remains unresolved.

http://baltimore.cbslocal.com/2012/11/14/debate-over-license-plate-readers-grows-in-maryland/

http://www.aclu.org/automatic-license-plate-readers-threat-americans-privacy

http://www.aclu.org/maps/automatic-license-plate-readers-are-you-being-followed

Boston police are spying on Americans, and storing thousands of license plates for intelligence purposes:

http://massprivatei.blogspot.com/2012/09/boston-police-are-spying-on-americans.html

Canadian privacy commissioner ruled Victoria Police use of license plate scanners violates the law.

The use of Automated License Plate Recognition (ALPR, also known as ANPR in the UK) is coming under increasing scrutiny in North America. The American Civil Liberties Union in July began requesting data from law enforcement agencies around the country so the activist group's lawyers could examine data collection policies. On Thursday, British Columbia, Canada's Information and Privacy Commissioner released the results of an official audit that took six months to look at whether use of the devices by the Victoria Police Department violates the law.

Commissioner Elizabeth Denham opened her inquiry after receiving a number of requests from concerned members of the public. She focused on determining whether use of cameras to track and store license plate data from all passing vehicles, even when their occupants were not suspected of any crime, was permissible under Canada's Freedom of Information and Protection of Privacy Act (FIPPA).

"Once a government has personal information, it may seek to find new uses for that information," Denham wrote. "This phenomenon, known as 'function creep,' is being made increasingly easier as information technology develops newer and more sophisticated means to 'mine' data for useful or interesting patterns, or to link databases of information. For these reasons, privacy laws such as FIPPA seek to protect against function creep by limiting government bodies to collecting only personal information that is necessary for their present programs."

In theory, passing vehicles are checked against a list of stolen or otherwise wanted cars. When the scanned plates matches a plate on the list, it is called a "hit" which triggers an alert for the police officer using the device. Cars not on the list are labeled as "non hits." Denham ruled police may not store data related to non-hits under FIPPA.

"I find that disclosure of non-hit personal information by Victoria Police to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police is not for a law enforcement purpose, and is therefore not authorized by FIPPA," Denham concluded.

Victoria Police claimed license plate data is not personal information subject to protection. The argument is undermined by a Royal Canadian Mounted Police privacy impact assessment that says license plate data is personal information.

British Columbia is not alone in seeking limits to the use of plate scanning devices. Denham noted Ontario limits the use of ALPR to "hit" data, and the states of Maine and New Hampshire restrict use to specific criminal investigations and do not allow random or routine searchers.

Investigation report: http://thenewspaper.com/rlc/docs/2012/can-vicalpr.pdf