Data brokers know more about you than your friends.

Data companies are scooping up enormous amounts of information about almost every American. They sell information about whether you're pregnant or divorced or trying to lose weight, about how rich you are and what kinds of cars you have.

Regulators and some in Congress have been taking a closer look at these so-called data brokers — and are beginning to push the companies to give consumers more information and control over what happens to their data.

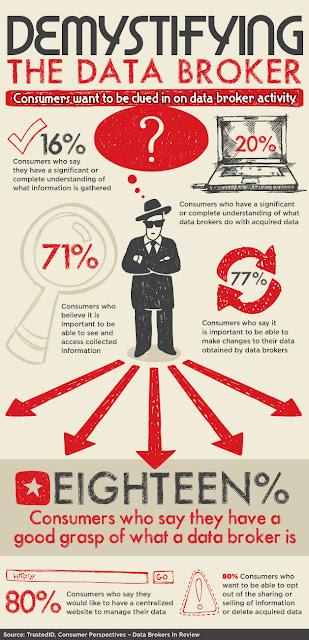

But many people still don't even know that data brokers exist.

Here's a look at what we know about the consumer data industry.

They start with the basics, like names, addresses and contact information, and add on demographics, like age, race, occupation and "education level," according to consumer data firm Acxiom's overview of its various categories.

But that's just the beginning: The companies collect lists of people experiencing "life-event triggers" like getting married, buying a home, sending a kid to college — or even getting divorced.

Credit reporting giant Experian has a separate marketing services division, which sells lists of "names of expectant parents and families with newborns" that are "updated weekly."

The companies also collect data about your hobbies and many of the purchases you make. Want to buy a list of people who read romance novels? Epsilon can sell you that, as well as a list of people who donate to international aid charities.

A subsidiary of credit reporting company Equifax even collects detailed salary and paystub information for roughly 38 percent of employed Americans, as NBC news reported. As part of handling employee verification requests, the company gets the information directly from employers.

Equifax said in a statement that the information is only sold to customers "who have been verified through a detailed credentialing process." It added that if a mortgage company or other lender wants to access information about your salary, they must obtain your permission to do so.

Of course, data companies typically don't have all of this information on any one person. As Acxiom notes in its overview, "No individual record ever contains all the possible data." And some of the data these companies sell is really just a guess about your background or preferences, based on the characteristics of your neighborhood, or other people in a similar age or demographic group.

The stores where you shop sell it to them.

Datalogix, for instance, which collects information from store loyalty cards, says it has information on more than $1 trillion in consumer spending "across 1400+ leading brands." It doesn't say which ones. (Datalogix did not respond to our requests for comment.)

Data companies usually refuse to say exactly what companies sell them information, citing competitive reasons. And retailers also don't make it easy for you to find out whether they're selling your information.

But thanks to California's "Shine the Light" law, researchers at U.C. Berkeley were able to get a small glimpse of how companies sell or share your data. The study recruited volunteers to ask more than 80 companies how the volunteers' information was being shared.

Only two companies actually responded with details about how volunteers' information had been shared. Upscale furniture store Restoration Hardware said that it had sent "your name, address and what you purchased" to seven other companies, including a data "cooperative" that allows retailers to pool data about customer transactions, and another company that later became part of Datalogix. (Restoration Hardware hasn't responded to our request for comment.)

Walt Disney also responded and described sharing even more information: not just a person's name and address and what they purchased, but their age, occupation, and the number, age and gender of their children. It listed companies that received data, among them companies owned by Disney, like ABC and ESPN, as well as others, including Honda, HarperCollins Publishing, Almay cosmetics, and yogurt company Dannon.

But Disney spokeswoman Zenia Mucha said that Disney's letter, sent in 2007, "wasn't clear" about how the data was actually shared with different companies on the list. Outside companies like Honda only received personal information as part of a contest, sweepstakes, or other joint promotion that they had done with Disney, Mucha said. The data was shared "for the fulfillment of that contest prize, not for their own marketing purposes."

Your state Department of Motor Vehicles, for instance, may sell personal information — like your name, address, and the type of vehicles you own — to data companies, although only for certain permitted purposes, including identify verification.

Public voting records, which include information about your party registration and how often you vote, can also be bought and sold for commercial purposes in some states.

Data companies can capture information about your "interests" in certain health conditions based on what you buy — or what you search for online. Datalogix has lists of people classified as "allergy sufferers" and "dieters." Acxiom sells data on whether an individual has an "online search propensity" for a certain "ailment or prescription."

Consumer data is also beginning to be used to evaluate whether you're making healthy choices.

One health insurance company recently bought data on more than three million people's consumer purchases in order to flag health-related actions, like purchasing plus-sized clothing, the Wall Street Journal reported. (The company bought purchasing information for current plan members, not as part of screening people for potential coverage.)

Spokeswoman Michelle Douglas said that Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina would use the data to target free programming offers to their customers.

Douglas suggested that it might be more valuable for companies to use consumer data "to determine ways to help me improve my health" rather than "to buy my data to send me pre-paid credit card applications or catalogs full of stuff they want me to buy."

As the FTC notes, "There are no current laws requiring data brokers to maintain the privacy of consumer data unless they use that data for credit, employment, insurance, housing, or other similar purposes."

As we highlighted last year, some data companies record — and then resell — all kinds of information you post online, including your screen names, website addresses, interests, hometown and professional history, and how many friends or followers you have.

Acxiom said it collects information about which social media sites individual people use, and "whether they are a heavy or a light user," but that they do not collect information about "individual postings" or your "lists of friends."

More traditional consumer data can also be connected with information about what you do online. Datalogix, the company that collects loyalty card data, has partnered with Facebook to track whether Facebook users who see ads for certain products actually end up buying them at local stores, as the Financial Times reported last year.

http://www.propublica.org/article/everything-we-know-about-what-data-brokers-know-about-you