Forensic science in the U.S. are we using "junk science" to put people behind bars?

Massachusetts is not the only state to experience a recent problem in its crime lab. Earlier this year, the drug lab in St. Paul, Minnesota, was shut down after problems developed with possible evidence contamination. The state lab had to take over the case work. Michigan’s state crime lab faces the same problem. Since the Detroit crime lab closed in 2008, the Michigan State Police lab has been handling all the forensic evidence collected at Detroit crime scenes, as well as trying to work through 11,000 untested rape kits that were discovered in the Detroit lab before it closed.

The ramifications extend far beyond the labs themselves. Before evidence is admitted into a trial record, a judge must determine whether the evidence is scientifically valid and evaluate its relevance to the case. In 1993, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed that judges are in fact the gatekeepers against “junk science” in the courtroom and identified them as the final arbiter of what constitutes valid scientific evidence.

This is a problem, says Judge Donald Shelton, a trial court judge in Michigan’s Washtenaw County and author of several books on forensic evidence. Many, if not most judges, lack the skill to evaluate forensic evidence properly.

“Many judges don’t have (flawed forensics) on their radar yet, and our judicial education is spotty from state to state,” says Shelton. “We, as judges, owe it to ourselves to become much better informed about the current state of forensic science.”

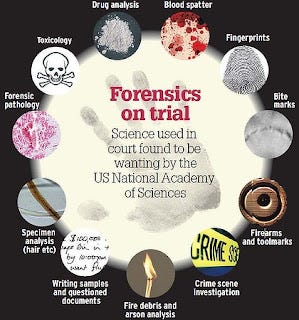

In fact, the whole field of forensic science is currently in flux, following a top-to-bottom review in 2009 by the National Academy of Sciences. The report cast major doubt on many common forensic techniques, calling them unscientific and error-prone.

Specifically, bite mark analysis, where perpetrators are identified by matching a mold of their teeth to bite marks found on a victim’s body, was found to be entirely unscientific and subject to an individual examiner’s interpretation. Another common technique, analyzing hair evidence, was found to be ineffective at producing any individual match, although it can potentially narrow the field of suspects to people who share certain hair characteristics, like color, hair-shaft form or length.

While the results have shaken up the forensic science community, Judge Shelton says that the effect on the courts hasn’t set in yet. “One of my concerns, “he says, “is that these forms of evidence that we know from the National Academy of Sciences report aren’t valid, are still routinely offered and routinely admitted by judges.”

The problem courts face is that juries now demand forensic evidence before they can be convinced that the police did their job investigating a crime. This is what many judges and prosecutors are coming to call the “CSI effect,” the expectations of a jury that all trials will have foolproof scientific evidence establishing guilt or innocence. Shelton, who has conducted multiple studies on the effects of forensic evidence on juries, calls it a broader “technology effect,” where jurors want to see forensic evidence as a result of the advances in science and technology they use in their own lives.

This effect of forensics on cases is all the more magnified during the plea bargaining process, where forensic evidence, whether solid or faulty, can be enough to convince defendants to plead guilty to a crime they may or may not have committed.

“Particularly in low level crime, like in the drug cases now in question in Boston, the likelihood that the prosecutor says ‘This is cocaine’ and the defendant can’t prove otherwise, that means they’ll plead,” says Jennifer Laurin, a law professor at the University of Texas at Austin. “The simpler the crime,” Laurin says, the more likely that “forensics are going to be dispositive.”

But for all the faults in forensics and the crime lab process, prosecutors warn strenuously against disregarding certain forensic evidence or techniques as a reaction to a few high-profile wrongful convictions. “It’s ridiculous to say that fingerprint evidence isn’t reliable,” says Scott Burns, head of the National District Attorneys Association. “Or that tool marks, ballistics, or all those pieces of evidence shouldn’t be introduced. In any trial, each piece of fact is going to be assessed. If we throw all that evidence out, there’s not going to be too many criminal trials in this country.”

But carefully evaluating forensic evidence in criminal cases, even at a time when courts are under pressure from budget cuts and high caseloads, is fundamentally important, Shelton says. “In civil trials, it’s only money at stake. In criminal cases, we are going to lock someone up or execute them based on that evidence.”

http://www.pewstates.org/projects/stateline/headlines/forensic-science-falls-short-of-public-image-first-of-two-parts-85899431908

D.C. crime lab: An experiment in forensic science.

It’s a $210 million facility, more than 10 years in the works. Dr. Max Houck, the director of the D.C. Department of Forensic Science, talks about it in grand terms. “We have the potential,” he says, "to act as an example that a public, independent laboratory can function as a public good.”

Such enthusiasm might be understandable for the head of a new installation like this, but it’s rare right now among crime lab directors anywhere in America. They have watched their profession go through serious turbulence in the last few years. Most recently, a crime lab chemist in Massachusetts confessed to falsifying drug test results and forging other analysts’ signatures on lab documents to speed up evidence testing. A report issued by the National Academy of Sciences in 2009 questioned the entire underpinning of many established forensic science techniques.

While morale in the field is generally low, D.C. is aiming high. Its Department of Forensic Science, the city’s newest agency, is the first in the country to incorporate many of the Academy’s recommendations. Staffed solely by civilian scientists, it will take over crime scene investigation from the city’s beleaguered Police Department and bring DNA testing back into the District. Until this October, DNA testing had been outsourced to a lab in Lorton, Virginia, causing a major backlog in rape kit analysis. At its worst, the backlog in rape kits extended more than three years, according to testimony from a rape crisis counselor in front of the D.C. Council Judiciary Committee.

“When I talk to other forensic scientists about the new department,” says Houck, “they become visibly excited at the prospect of a jurisdiction finally ‘getting it right.’”

All this was made possible by legislation that passed the D.C. Council last year, promoted by Councilmember Phil Mendelson. “The public in general does not appreciate how much in the dark ages forensic science is and the general impression is that forensics is what you see on T.V.,” says Mendelson. “We’re fortunate that we have both the legislation creating the new agency and the new lab—the two together have put us in position where the District will be at the forefront (of forensic science).”

The District is no stranger to problems with faulty forensic evidence. In 2010, Donald E. Gates was exonerated after serving 28 years in prison for a rape and murder in Washington’s Rock Creek Park that he did not commit. He was convicted in 1982 in D.C. Superior Court based on hair evidence found on the victim’s body, which an FBI analyst testified was “microscopically indistinguishable” from Gates’ hair.

But hair fiber analysis was later shown to be faulty. According to the National Academy of Sciences report, hair analysis is only conclusive enough to show that a hair belongs to someone with certain characteristics. It can’t be used to identify a specific person. That finding led to Gates’ exoneration and is leading the D.C. lab to rethink how it characterizes hair and fiber evidence.

“Hair examinations have a place in forensic science,” says Houck, “but they cannot be used to identify someone and should not be characterized as such, either by scientists or by attorneys.”

The same year that Gates was exonerated, a consultant to the D.C. police department discovered that the roadside testing equipment used by police officers to detect alcohol on a driver’s breath had not been properly calibrated and was issuing inflated blood alcohol content readings. At least 400 cases were identified by the District attorney general’s office as potentially involving incorrect breath tests, and 50 people challenged their cases in court. Two people were exonerated.

Talks about creating a forensic science agency were in the works years before the problems with the breath tests emerged, but they added to the need for the department, says Mendelson. The legislation creating the agency specifically directs the Department of Forensic Sciences to oversee the calibration of the breath tests, and the department has signed a memorandum of understanding with the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner to calibrate the testing equipment.

Traditionally, states and other jurisdictions have kept crime labs tied to the police or the prosecutor’s office both for logistical and budgetary reasons. It’s easier for police officers to drop off evidence if the crime lab is in the same building as the police department, says Jessica Gabel, assistant professor of law at Georgia State University. And it’s easier for states to allocate funding to law enforcement agencies and then have them disperse money to the crime labs.

But that closeness costs labs in other ways. “Crime labs don’t get evidence in a vacuum,” says Gabel. “They hear that someone’s killed a child, and the pressure’s on (to identify the killer).”

The closeness between crime labs and police can also open labs up to harsh criticism, says Mendelson. “If the crime lab is within the police department, defense attorneys could say to an analyst, ‘well, you work for law enforcement, you’re just proving the police officer’s case.’ It’s better for the justice system when forensic analysis is done by a separate agency.”

A few states, including Virginia and Rhode Island, do operate their crime labs separately from law enforcement. But those states have always been seen as exceptions to standard practice. Now, Houck believes, D.C.’s civilian-led crime lab can point the way to similar changes in crime labs across the country.

“We need a national strategy on forensic science,” he says. “Our strategy can’t simply be more money and neither can it be, ‘let’s hope we don’t screw up.’ Here, we are running the agency as a science-based organization and as a peer with other agencies like the medical examiner or law enforcement with the focus really being on the science.”

http://www.pewstates.org/projects/stateline/headlines/dc-crime-lab-an-experiment-in-forensic-science-second-of-two-parts-85899432291