Interview with the filmmaker of the war on drugs movie - The House I Live In.

By Maya Schenwar:

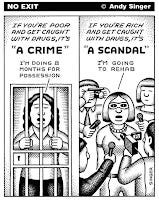

How do you make a film about a subject as expansive and many-tentacled as the drug war? Do you focus on its circuitous history? The injustices of sentencing? The destructive effects on families and communities? The profit motives that fuel the system? The impact on policing, law enforcement and public safety? The ways in which entrenched racism and classism dictate the system's targets? The answer for filmmaker Eugene Jarecki was a whopping "all of the above." In the stunning "The House I Live In," he depicts the vast sweep of this insidious campaign's effects, while portraying the nuanced – often conflicted – views of the political and economic players who perpetuate it. The film delivers a multi-dimensional picture of an issue of which we're usually able to view only slices, demonstrating, in sum, the colossal failure of the 40-year "war on drugs." I got on the phone with Jarecki to discuss the film, and how he is using it as a tool to spark tangible action.

Maya Schenwar: "The House I Live In" covers such a massive and complex topic, and you captured that complexity while showing that there is a very clear verdict as to whether or not the war on drugs has worked. Sometimes when progressives talk about these issues, the evils of the system seem to get personified in this way that's not helpful (the police are "evil," a particular judge or politician is "evil," etc.). But you interviewed police, prison guards, judges - all those folks - and you didn't hear the things we might expect to hear from them. So, I'm wondering, how did you decide who to interview, and what was that process of decision-making like?

Eugene Jarecki: I wanted to portray the fullness of the issue. As the drug war has grown over time, it's like any predatory monster; it knows no bounds. I was convinced from early on we needed to travel far and wide and talk to people at all levels of the drug war, from the dealer and the user to family members to community members to cops, jailers, judges, lawyers, wardens and then - ultimately - to policymakers.

I wanted to see how people inside the system felt, far more than I wanted to hear from critics. There are critical voices in the film, people like David Simon and Richard Miller and Charles Ogletree and Michelle Alexander - very smart critics who put what the viewer sees in the larger political and historical context - but what mattered most to us was the firsthand experience and testimony of the people whose stories are wrapped up in this issue.

People surprised us greatly. You go into the prison system and you think, well, the people who run Corrections, they'll be the real "tough on crime" people, and they'll explain to me how they see the world, which will stand in great opposition to the way a drug dealer I just spoke to sees the world. But we found out how many people on the inside, up and down the chain of command, viewed the system deeply critically. That was unexpected, and that became the most inspiring part of making the film.

Almost no one believes in this system. In looking for diversity - crossing the country and encountering so many different walks of life and so many geographies - I ended up finding an extraordinary unanimity: the idea that the drug war has been with us for 40 years, we've spent a trillion dollars on it, we've had 45 million drug arrests, and we have nothing to show for it. So, it was almost impossible to find someone who would defend a record like that.

MS: Wow. Did you meet anyone who did wholeheartedly defend it?

EJ: No. The only people who come close to wholehearted defense - and it's halfhearted defense in their case, honestly - are the people on the profiteering side of the war on drugs, whose livelihood depends on it. So, as in so many professions that have a dark subtext, they've developed a sort of Orwellian doubletalk, to euphemize and obfuscate about what they do. They have all kinds of prepared argumentation about the benefits of the way in which they profit from it, the services they provide. Their phone services are better, or they sell a better stun gun than the other stun gun, or their restraint chair is better than the old kind of restraint chair that another company made. At the micro level, they may all have something to say about how they're making a better good or service at a better value, but it is within what even they would recognize is not the best way to make a living - it's probably not the career they dreamed of when they were in high school.

Read more:

http://truth-out.org/news/item/12707-the-people-vs-the-war-on-drugs-filmmaker-tackles-the-predatory-monster