It's time to consider closing America's fusion centers.

Article first appeared in the PrivacySos.org website:

Do we need so-called intelligence fusion centers? A senate subcommittee for investigations report published in 2012 pointed out that the centers are extremely costly, duplicative of other federal-local intelligence and terrorism efforts, and have been shown to infringe on civil liberties.

Our recent history with fusion centers here in Boston backs up all of those findings.

After the Boston Marathon bombings, the press was quick to ask: where were the fusion centers? We have two in Massachusetts; there is one state-run center, the Commonwealth Fusion Center (CFC), and one run by the Boston Police, the Boston Regional Intelligence Center (BRIC).

The FBI’s response to the question “Where were the fusion centers?” is extremely illuminating:

A spokeswoman for the Boston Police Department said the Boston Regional Intelligence Center [] was never notified about the FBI investigation.

In response, FBI supervisory Agent Jason Pack e-mailed a statement suggesting that state and local officials had ample access to information about the Tsarnaev investigation in 2011, through their participation in an FBI unit in Boston, the Joint Terrorism Task Force.

“Many state and local departments directly involved and affected by the Boston Marathon investigation have representatives who are full-time members of the JTTF and who have the same unrestricted access to information and government databases as their FBI colleagues,’’ Pack said. “State and local JTTF representatives were assigned to the squad that conducted the 2011 assessment.’’

That’s right: the FBI had shared information about Tsarnaev with its state and local partners, through the Joint Terrorism Task Force. The fusion center wasn’t notified, and the FBI doesn’t apologize for this. That leads me to believe that the FBI doesn’t think that leaving the fusion centers out of the loop on terrorism investigations is a problem that requires fixing.

If the FBI’s investigatory work with state and locals on terrorism is situated at the JTTFs, as it appears to be, what useful purpose do fusion centers serve with respect to terrorism? The jury is out on that question. But we know a bit about some non-terrorism related activities at the BRIC.

A public records lawsuit in 2011 showed that the Boston Regional Intelligence Center, like other fusion centers nationwide, devoted resources and time to spying on perfectly peaceful dissenters like Veterans for Peace and Code Pink.

In light of bad press resulting from the senate subcommittee report, and declining federal funds, some fusion centers are waking up to the realization that they may have to rely on state and local funding to continue operations.

In Wisconsin, federal funding for fusion centers has decreased 88% since 2005. Governor Scott Walker is pledging to fill in the gap with state funding, at a time when public services are being cut statewide.

But it’s not at all clear that fusion centers are worth the money, and they may in fact be harmful to our society. Instead of continuing to fund them, we should pause and reflect on whether the institutions are worth the cost to our liberty and our pocketbooks. The evidence here in Boston suggests it may be time to stop throwing money at them once and for all.

http://privacysos.org/node/1053

Fusion center director admits to spying on ‘anti-government’ Americans:

Have you ever complained about the government? If yes, then hopefully you don’t live in Arkansas.

The goal of fusion centers “is to collect and share information, to prevent bad things from happening,” said Richard Davis, the director of the Arkansas State Fusion Center. He was teaching First Responders about Intelligence gathering techniques when he stated:

“There’s misconceptions on what fusion centers are. The misconceptions are that we are conducting spying operations on US citizens, which is of course not the fact. That is absolutely not what we do.”

Davis says Arkansas hasn’t collected much information about international plots, but they do focus on groups closer to home.

“We focus a little more on that, domestic terrorism and certain groups that are anti-government,” he says. “We want to kind of take a look at that and receive that information.”

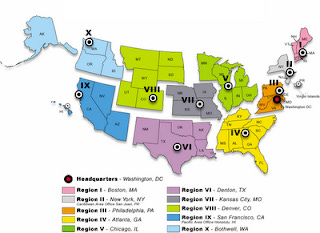

“Fusion centers,” according to the Department of Homeland Security, “conduct analysis and facilitate information sharing, assisting law enforcement and homeland security partners in preventing, protecting against, and responding to crime and terrorism.” A two-year investigation into fusion centers by the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs permanent subcommittee stated [PDF] that it "could identify no reporting which uncovered a terrorist threat, nor could it identify a contribution such fusion center reporting made to disrupt an active terrorist plot."

Furthermore, fusion centers "often produced irrelevant" and "useless" intelligence reports. "Many produced no intelligence reporting whatsoever." It was also confirmed by a former fusion center chief, who said, "There were times when it was, 'what a bunch of crap is coming through'."

DHS fusion center facts state, “Both Fusion Center Directors and the federal government identified the protection of privacy, civil rights, and civil liberties (P/CRCL) as a key priority and an important enabling capability to ensure fusion centers protect the privacy and other legal rights of Americans, while supporting homeland security efforts.”

Yet a recent Government Accountability Office study [PDF] into fusion centers has more First-Amendment-protected activities listed as potentially suspicious (nine), than it has as activities that are “defined as criminal and potential terrorism nexus activity” (seven). Those nine are listed as “these activities are generally First-Amendment-protected activities and should not be reported in a SAR or ISE (terrorism)-SAR absent articulable facts and circumstanced that support the source agency’s suspicion that the behavior observed is not innocent, but rather reasonable indicative of criminal activity associated with terrorism.”

The activities listed above are part of the reason that U.S. citizens feel that fusion centers are “spying” on them. According to the GAO report, the “DOJ had not fully assessed its training provided to officers on the front line, which could help ensure that officers receive sufficient information to be able to recognize terrorism-related suspicious activity. DOJ has provided training to executives at 77 of 78 fusion centers, about 2,000 fusion center analysts, and about 290,000 of the 800,000 line officers. DOJ is behind schedule in training the line officers but is taking actions to provide training to officers who have not yet received it.”

Additionally, the GAO report found that suspicious activity reports (SARs) can be submitted through two different systems, the DOJ's Shared Spaces and the FBI’s eGuardian, meaning that the FBI might not receive the “needed information.” The GAO found that of “74 fusion centers, three submit reports through Shared Spaces only and not to eGuardian, and 23 centers submit to Shared Spaces in all cases and to eGuardian on a case-by-case basis.”

Although the GAO recommended that the DOJ mitigate risks of supporting two servers, “officials at one fusion center said they use DOJ's Shared Spaces because it allows them to remove suspicious activity reports at their discretion, thus removing it from federated search and complying with their privacy policy.”

http://blogs.computerworld.com/privacy/21991/fusion-center-director-admits-spying-anti-government-americans