Microsoft releases report on law enforcement requests

US law enforcement is the biggest recipient of Microsoft customer data.

Microsoft disclosed for the first time on Thursday the number of requests it had received from government law enforcement agencies for data on its hundreds of millions of customers around the world, joining the ranks of Google, Twitter and other Web businesses that publish so-called transparency reports.

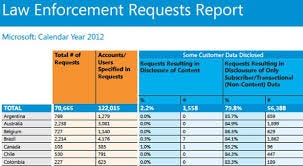

The report, which Microsoft said it planned to update every six months, showed that law enforcement agencies in five countries — Britain, France, Germany, Turkey and the United States — accounted for 69 percent of the 70,665 requests the company received last year.

Microsoft responds to requests for data in 46 countries, those where it says it can properly verify the legitimacy of the requests. In 2012, a total of 70,665 requests were made. The country making the most demands for data was Turkey, with 11,434. The US was in second place, with 11,073. Each request could concern multiple users, with a total of 122,015 users covered by requests.

When it comes to the number of requests that returned customer data, however, the US was the clear leader. Of 1,558 requests that resulted in disclosure of some customer content, such as the subject or body of an e-mail or a photograph on SkyDrive, 1,544 were made in the US. The other 14 were split between Brazil (7), Canada (1), Ireland (5), and New Zealand (1).

In 80 percent of requests, Microsoft provided elements of what is called noncontent data, like an account holder’s name, sex, e-mail address, I.P. address, country of residence, and dates and times of data traffic.

In 2.1 percent of requests, the company disclosed the actual content of a communication, like the subject heading of an e-mail, the contents of an e-mail or a picture stored on SkyDrive, its cloud computing service.

“Government requests for online data are like the dark matter of the Internet,” said Eva Galperin, a global policy analyst at the Electronic Frontier Foundation in San Francisco, which has campaigned for greater disclosure.

Ms. Galperin said that even with Microsoft’s disclosures, fewer than 10 companies published the extent of their cooperation with law enforcement agencies.

“Only a few companies report this, but they are only a very small percent of the online universe,” she said. “So any one company that joins the disclosure effort is good news. The faster this becomes a standard for all Web businesses, the better.”

The law enforcement requests concerned users of Microsoft services including Hotmail, Outlook.com, SkyDrive, Skype and Xbox Live, where people are typically asked to enter their personal details to obtain service.

Google was the first major Web business, in 2010, to report the number of legal requests it had received for information. Since then, Twitter, LinkedIn and some smaller companies have also begun reporting, but big businesses like Apple and Yahoo have not.

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/03/22/technology/microsoft-releases-report-on-law-enforcement-requests.html?pagewanted=all&_r=3&

Justice Dept. backs rewriting law that allows police to read emails:

The Justice Department said on Tuesday that it supports rewriting 26-year-old legislation that has allowed US law enforcement officials to read a person's emails without a search warrant so long as the email is older than six months or already opened.

The law has long been criticized by privacy advocates as a loophole when it comes to protecting Americans from government snooping.

"There is no principled basis to treat email less than 180 days old differently than email more than 180 days old," Elana Tyrangiel, acting assistant attorney general in the Office of Legal Policy, told a House judiciary subcommittee. She also said emails deserve the same legal protections whether they have been opened or not.

Tyrangiel's testimony gives Congress a starting point as it begins to review a complicated 1986 law known as the Electronic Communications Privacy Act.

Written at a time before the internet was popularized and before many Americans used Yahoo or Google servers to store their emails indefinitely, the law allows federal authorities to obtain a subpoena approved by a federal prosecutor – not a judge – to access electronic messages older than 180 days.

The Justice Department also has interpreted the law to mean that law enforcement with only a subpoena can review emails that have already been opened by the user, although that has been challenged by the courts.

"The truth is that no one has put forward any evidence of pervasive law enforcement abuse of ECPA provisions," Littlehale told the House panel.

But privacy advocates and technology companies like Google, Twitter and Dropbox have complained that law enforcement has gone too far. Google says government demands for emails and other information held on its servers increased 136 percent since 2009.

"We recognize that local, state and law enforcement agencies have legitimate needs for data," said Richard Salgado, Google's director of law enforcement and information security. "We also recognize the need to ensure that disclosure laws, such as ECPA, properly honor the privacy that users of communications services reasonably expect."

A George Washington University law professor, Orin Kerr, told the panel that any new law should limit what data is disclosed to law enforcement, even if a warrant were obtained. Currently, he said, a technology company will send the government the entire contents of a person's email account.

"Investigators can scan through all the contents of a person's digital life without limit," Kerr said.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/law/2013/mar/19/justice-department-police-read-email