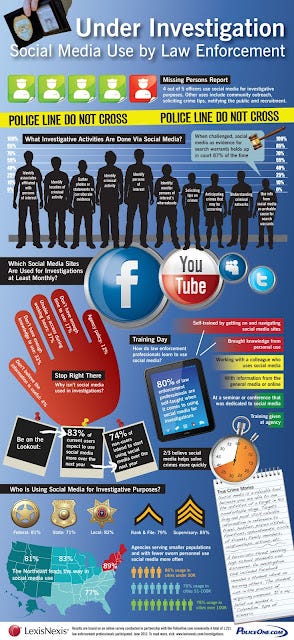

Police are spying on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, PInterest & other social media platforms.

(image: http://www.lexisnexis.com/government/investigations/)

Monterey Park, CA - On a cold and drizzly morning at the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Headquarters Bureau, a 25-year-old social media dispatcher is sitting at a computer station in a dimly lit room skimming social media feeds on three large screens.

The tech-savvy civilian dispatcher is part of the bureau's new, 24-hour Electronic Communications Triage or eComm Unit that monitors social media and Internet content, shares information with the public and trains sheriff's officials to use such platforms.

"They're watching social media and Internet comments that pertain to this geographic area, watching what would pertain to our agencies so we can prevent crime, help the public," LASD Capt. Mike Parker said. "And now they're going to be ramping up more and more with more sharing and interacting, especially during crises, whether it's local or regional."

Since launching last September, the eight-member eComm unit has identified a suicidal teen on Instagram, intercepted bomb threats made on Twitter and discovered plans for hundreds of illegal drug parties via Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.

Social media has also been used to track and locate youth that have indicated they may be suicidal. Last year, the Arcadia Police Department was notified after a Colorado teen, a member of a network of volunteers in search of Tumblr.com users in danger of suicide or depressed, saw that a teenager in Arcadia had posted a photo of herself on Tumblr with cut-up wrists and alarming messages.

During the search for ex-fugitive cop Christopher Dorner, the unit promoted messages to the public put out by investigating agencies and forwarded clues they spotted on social media to investigators.

At least one social media dispatcher is on duty at all times monitoring content related to keywords of interest, such as LASD and school lockdown, for example.

While many law enforcement agencies monitor social media for criminal activity, Parker said the L.A. County Sheriff's Department is the only agency he's aware of that is monitoring it around the clock and in such a comprehensive way.

In a survey last year of 1,200 federal, state and local law enforcement professionals, four out of five respondents acknowledged using various social media platforms to assist in investigations. The LexisNexis Risk Solutions survey also found that 67 percent of respondents believe social media helps solve crimes more quickly.

Besides using it for investigations, local law enforcement agencies are increasingly turning to social media for "preventive" or "intelligence-led" policing to pre-empt illegal drug parties or unsanctioned protests.

"It's a smart move," Karen North, director of USC's Annenberg Program on Online Communities, said. "All people should know that anything you put up on social media is public. Even if you put it up on your private Facebook feed, you should still assume it's public" since private messages or photos can ultimately be shared by others.

The police have a very bright future ahead of them – and not just because they can now look up potential suspects on Google. As they embrace the latest technologies, their work is bound to become easier and more effective, raising thorny questions about privacy, civil liberties, and due process.

For one, policing is in a good position to profit from "big data". As the costs of recording devices keep falling, it's now possible to spot and react to crimes in real time. Consider a city like Oakland in California. Like many other American cities, today it is covered with hundreds of hidden microphones and sensors, part of a system known as ShotSpotter, which not only alerts the police to the sound of gunshots but also triangulates their location. On verifying that the noises are actual gunshots, a human operator then informs the police.

It's not hard to imagine ways to improve a system like ShotSpotter. Gunshot-detection systems are, in principle, reactive; they might help to thwart or quickly respond to crime, but they won't root it out. The decreasing costs of computing, considerable advances in sensor technology, and the ability to tap into vast online databases allow us to move from identifying crime as it happens – which is what the ShotSpotter does now – to predicting it before it happens.

Instead of detecting gunshots, new and smarter systems can focus on detecting the sounds that have preceded gunshots in the past. This is where the techniques and ideologies of big data make another appearance, promising that a greater, deeper analysis of data about past crimes, combined with sophisticated algorithms, can predict – and prevent – future ones. This is a practice known as "predictive policing", and even though it's just a few years old, many tout it as a revolution in how police work is done. It's the epitome of solutionism; there is hardly a better example of how technology and big data can be put to work to solve the problem of crime by simply eliminating crime altogether. It all seems too easy and logical; who wouldn't want to prevent crime before it happens?

Police in America are particularly excited about what predictive policing – one of Time magazine's best inventions of 2011 – has to offer; Europeans are slowly catching up as well, with Britain in the lead. Take the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD), which is using software called PredPol. The software analyzes years of previously published statistics about property crimes such as burglary and automobile theft, breaks the patrol map into 500 sq ft zones, calculates the historical distribution and frequency of actual crimes across them, and then tells officers which zones to police more vigorously.

It's much better – and potentially cheaper – to prevent a crime before it happens than to come late and investigate it. So while patrolling officers might not catch a criminal in action, their presence in the right place at the right time still helps to deter criminal activity. Occasionally, though, the police might indeed disrupt an ongoing crime. In June 2012 the Associated Press reported on an LAPD captain who wasn't so sure that sending officers into a grid zone on the edge of his coverage area – following PredPol's recommendation – was such a good idea. His officers, as the captain expected, found nothing; however, when they returned several nights later, they caught someone breaking a window. Score one for PredPol?

Trials of PredPol and similar software began too recently to speak of any conclusive results. Still, the intermediate results look quite impressive. In Los Angeles, five LAPD divisions that use it in patrolling territory populated by roughly 1.3m people have seen crime decline by 13%. The city of Santa Cruz, which now also uses PredPol, has seen its burglaries decline by nearly 30%. Similar uplifting statistics can be found in many other police departments across America.

Other powerful systems that are currently being built can also be easily reconfigured to suit more predictive demands. Consider the New York Police Department's latest innovation – the so-called Domain Awareness System – which syncs the city's 3,000 closed-circuit camera feeds with arrest records, 911 calls, licence plate recognition technology, and radiation detectors. It can monitor a situation in real time and draw on a lot of data to understand what's happening. The leap from here to predicting what might happen is not so great.

If PredPol's "prediction" sounds familiar, that's because its methods were inspired by those of prominent internet companies. Writing in The Police Chief magazine in 2009, a senior LAPD officer lauded Amazon's ability to "understand the unique groups in their customer base and to characterise their purchasing patterns", which allows the company "not only to anticipate but also to promote or otherwise shape future behaviour". Thus, just as Amazon's algorithms make it possible to predict what books you are likely to buy next, similar algorithms might tell the police how often – and where – certain crimes might happen again. Ever stolen a bicycle? Then you might also be interested in robbing a grocery store.

Here we run into the perennial problem of algorithms: their presumed objectivity and quite real lack of transparency. We can't examine Amazon's algorithms; they are completely opaque and have not been subject to outside scrutiny. Amazon claims, perhaps correctly, that secrecy allows it to stay competitive. But can the same logic be applied to policing? If no one can examine the algorithms – which is likely to be the case as predictive-policing software will be built by private companies – we won't know what biases and discriminatory practices are built into them. And algorithms increasingly dominate many other parts of our legal system; for example, they are also used to predict how likely a certain criminal, once on parole or probation, is to kill or be killed. Developed by a University of Pennsylvania professor, this algorithm has been tested in Baltimore, Philadelphia and Washington DC. Such probabilistic information can then influence sentencing recommendations and bail amounts, so it's hardly trivial.

Legal scholar Andrew Guthrie Ferguson has studied predictive policing in detail. Ferguson cautions against putting too much faith in the algorithms and succumbing to information reductionism. "Predictive algorithms are not magic boxes that divine future crime, but instead probability models of future events based on current environmental vulnerabilities," he notes.

But why do they work? Ferguson points out that there will be future crime not because there was past crime but because "the environmental vulnerability that encouraged the first crime is still unaddressed". When the police, having read their gloomy forecast about yet another planned car theft, see an individual carrying a screwdriver in one of the predicted zones, this might provide reasonable suspicion for a stop. But, as Ferguson notes, if the police arrested the gang responsible for prior crimes the day before, but the model does not yet reflect this information, then prediction should be irrelevant, and the police will need some other reasonable ground for stopping the individual. If they do make the stop, then they shouldn't be able to say in court, "The model told us to." This, however, may not be obvious to the person they have stopped, who has no familiarity with the software and its algorithms.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/technology/2013/mar/09/facebook-arrested-evgeny-morozov-extract

http://www.sgvtribune.com/news/ci_22706138/local-cops-increasingly-turn-social-media-preventive-policing

(LexisNexis report) Law enforcement personnel use of social media in investigations: Summary of findings

http://images.solutions.lexisnexis.com/Web/LexisNexis/Infographic-Social-Media-Use-in-Law-Enforcement.pdf