Snitching on prisoners for personal gain, the growing business of selling information.

Atlanta, GA- The prisoners in Atlanta's hulking downtown jail had a problem. They wanted to snitch for federal agents, but they didn't know anything worth telling.

Fellow prisoner Marcus Watkins, an armed robber, had the answer.

For a fee, Watkins and his associates on the outside sold them information about other criminals that they could turn around and offer up to federal agents in hopes of shaving years off their prison sentences. They were paying for information, but what they were really trying to buy was freedom.

"I didn't feel as though any laws were being broken," Watkins wrote in a 2008 letter to prosecutors. "I really thought I was helping out law enforcement."

That pay-to-snitch enterprise – documented in thousands of pages of court records, interviews and a stack of Watkins' own letters – remains almost entirely unknown outside Atlanta's towering federal courthouse, where investigators are still trying to determine whether any criminal cases were compromised. It offers a rare glimpse inside a vast and almost always secret part of the federal criminal justice system in which prosecutors routinely use the promise of reduced prison time to reward prisoners who help federal agents build cases against other criminals.

Snitching has become so commonplace that in the past five years at least 48,895 federal convicts — one of every eight — had their prison sentences reduced in exchange for helping government investigators, a USA TODAY examination of hundreds of thousands of court cases found. The deals can chop a decade or more off of their sentences.

How often informants pay to acquire information from brokers such as Watkins is impossible to know, in part because judges routinely seal court records that could identify them. It almost certainly represents an extreme result of a system that puts strong pressure on defendants to cooperate. Still, Watkins' case is at least the fourth such scheme to be uncovered in Atlanta alone over the past 20 years.

Those schemes are generally illegal because the people who buy information usually lie to federal agents about where they got it. They also show how staggeringly valuable good information has become – prices ran into tens of thousands of dollars, or up to $250,000 in one case, court records show.

John Horn, the second in command of Atlanta's U.S. attorney's office, said the "investigation on some of these matters is continuing" but would not elaborate.

Prosecutors have said they were troubled that informants were paying for some of the secrets they passed on to federal agents. Judges are outraged. But the inmates who operated the schemes have repeatedly alleged that agents knew all along what they were up to, and sometimes even gave them the information they sold. Prosecutors told a judge in October that an investigation found those accusations were false. Still, court records show, agents kept interviewing at least one of Watkins' customers even after the FBI learned of the scheme.

People charged with federal crimes don't have many ways to avoid a tough sentence.

Nearly everyone charged is convicted. They usually face the prospect of a lengthy prison term, driven by long minimum sentences for drug crimes and sentencing rules that leave judges little leeway to make exceptions – unless they cooperate. Often, becoming an informant is the only chance defendants have.

An experienced lawyer who knows what his client has been charged with "can ask a client three or four questions, and you can get 95% accuracy on the sentencing range within 10 minutes … unless he has something to trade," said Tim Saviello, a John Marshall Law School professor and former federal public defender in Atlanta. "People are willing to pay $20,000 or $30,000 to get a piece of information. That tells you how valuable it is."

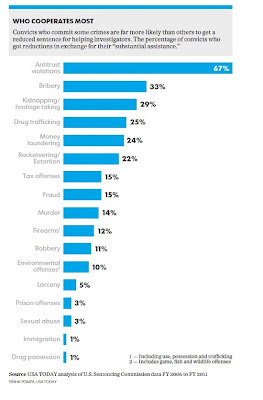

Every year for the past decade, 11% or more of the people convicted of a federal crime got a shorter sentence because they provided "substantial assistance" to investigators, a USA TODAY examination of federal sentencing data shows. That figure almost certainly understates the extent to which defendants cooperate because some get breaks that aren't reflected in court records and others only pass on information that the government doesn't find useful.

In return, prisoners offer up names and addresses of drug dealers. They wear recording devices or let police listen to their phone calls. They introduce undercover agents to their contacts inside crime organizations.

That kind of help has become indispensable for law enforcement. The Drug Enforcement Administration told the Justice Department's inspector general in 2005 that it "could not effectively enforce the controlled-substances laws of the United States" without its confidential sources.

Cooperation is especially common when drugs are involved. Nationwide, at least a quarter of the people sent to federal prison in drug-trafficking cases over the past five years successfully traded information for a shorter sentence. In some parts of the country – including Idaho, Colorado and western New York – more than half did, while in Nebraska, fewer than 5% of convicted drug traffickers got deals. One reason is that some prosecutors' offices demand far more cooperation to get a deal.

http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2012/12/14/jailhouse-informants-for-sale/1762013/

Interactive Map: The Big Business of Snitching.

Click to view U.S. map of federal convictions from 2006-2011 where sentences were cut for 'substantial assistance,' according to a USA TODAY investigation:

http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2012/12/13/informants-shorter-prison-sentences/1760881/

The FBI now spends more than 3 billion dollars a year on counter-terrorism, the bureau maintains a team of 15 thousand spies in a nationwide network of informants. Criminal informants or snitches are part of a criminal system most people know little about. Many of these informants are tasked with infiltrating Muslims communities in the United States. We’ve discussed in the past, the expanded FBI guidelines plus the broad over reaching powers and underhanded tactics the FBI use when targeting Mosques and Muslim Americans.

Professor of Law and author Alexandra Natapoff, talked about her book Snitching: Criminal Informants and the Erosion of American Justice (2009). Her book catalogs the downside in the use of snitches on social structure and democracy and suggests ways to make the use of informants acceptable within the criminal justice system.

Professor Alexandra Natapoff:

Snitching is such a massive part of our criminal justice system even though the public rarely gets a good look at it.

It’s an under the radar aspect of the way our criminal justice system handles investigations, the way it handles cases, the way it shapes our case law.

It’s such a powerful deal, a deal that exerts a huge amount of influence and plea bargaining.

The reality is that this is a deeply under-regulated arena. The handler is the law enforcement official who creates and uses an informant.

It could be a police officer talking to a street corner addict cutting a deal right then and there.

It could be an FBI agent who has an established documented supervised relationship with a long term criminal informant.

Somebody may be suspected of a crime or even just of interest to the government. People who have mild brushes with the criminal system can end up through this mechanism of criminal informing entering into a world in which really anything can happen to them.

Argument: Either you let us use informants in an unaccountable, invisible, secretive, undocumented way or we can’t run the criminal system at all.

We permit the barter of crime under the radar, in a way that is unfair to other defendants and other suspects. We produce unreliable information through the use of informants without regulation.

My contention is that we shouldn’t ban this practice, but run it as any other public policy with transparency and accountability and some rules.

My favorite criminal informant of recent is Jack Abramoff.

Usually we don’t learn when informants have been mistreated because often they have very little power.

The courts have said, informants proceed at their own risk.

This is a deal that they can enter if they want to risk their life.

The law does not owe criminal informants much protection. Our criminal system is built on the principle that the defendant should not have to face the government unaided by council.

That’s a principle that should be extended to criminal informants.

The state of Florida passed a ground breaking law, called Rachel’s Law.

What sort of deal should we permit the government to cut with informants?

The use of criminal informants is a massive source of error in capitol cases.

States across the country are starting to impose greater restrictions on the use of criminal informants, in particular jailhouse snitches as a way to improving reliability of the information.

Confidential Informant Accountability Act – Federal Legislative Proposal

One of the things the government doesn’t keep track of is how many crimes are committed by criminal informants in the pursuit of investigating new cases.

http://lawanddisorder.org/category/afghanistan-war/page/2/

Private school rewards snitches, parents say.

Houston, TX - A Christian high school rewards students for providing "covert intelligence" on classmates, and forced a girl to withdraw after a student spy falsely accused her of smoking pot, her parents claim in court.

David and Debra Mouton sued Houston Christian High School behalf of their daughter, C, in Harris County Court.

The parents also claim the school dean asked their daughter intrusive, sexual questions.

The Moutons say they paid $18,000 to enroll their daughter in the school based on representations in its student and parent handbooks.

"The student and parent handbooks provided to plaintiffs state the following about the so-called 'D-Group': This so called 'D-Group' is thus ostensibly in existence for the benefit of a student's personal religious growth.

"Not only does the so-called 'D-Group' receive accolades and special treatment for their covert activities, the reports made by the 'D-Group' members of alleged student misconduct are apparently relied on by defendant's administration as if they were fact.

"In (C's) case, a member of the 'D-Group' wrote a note to the administration accusing (C.M.) of smoking marijuana."

The Moutons say that in response to the allegations, their daughter voluntarily took three drug tests "all of which came back negative."

However, "Even after three drug tests proved that (C) had done nothing wrong, out of the presence of Dr. and Mrs. Mouton, and without their knowledge or consent, defendant's administration sequestered (C) in an office and coerced a 'confession' by offering her 'leniency' if she just fess-up," the complaint states.

"Fearing more accusations and interrogations, (C) gave in to the pressure and said she had 'tried something.' Then, in exchange for her forced confession, (C) was informed that she would either be expelled with a marijuana use reference, or that she could withdraw from defendant's school. (C) was thereby forced to withdraw, at which time she was held in the office of the school counselor, Carol Bertels, against her will, for at least an hour, while her locker was cleaned out and searched by the dean."

Though the school handbooks "clearly state that upon receiving a report of alleged student misconduct, the administration will conduct an investigation before taking disciplinary action," it uses "Gestapo-type tactics" to get confessions out of students, the Moutons say in the complaint.

"Defendant's institution even goes so far as to interrogate students, in the presence of their parents, regarding alleged and/or supposed sexual activities; even asking if certain photos are 'arousing' or words to that effect," the Moutons say.

"During one such sexual interrogation of (C), defendant's dean sequestered (C) in his office, shut the door, and out of the presence of (her) parents, asked (C) if she had engaged in oral sex with her boyfriend.

http://www.courthousenews.com/2012/12/10/52977.htm