The effects of privatization on the public of private prison lobbies (parts1-3).

By Sasha Volokh:

Private prison firms are often accused of lobbying for incarceration because, like a hotel, they have “a strong economic incentive to book every available room and encourage every guest to stay as long as possible” (Schlosser 1998; see also Dolovich 2005; Shichor 1995; Sarabi and Bender 2000). This accusation has little support, either theoretical or empirical. At worst, the political influence argument is backward: privatization will in fact decrease prison providers’ pro-incarceration influence. At best, the argument is dubious: its accuracy depends on facts that proponents of the argument haven’t developed.

First, self-interested pro-incarceration advocacy is already common in the public sector—chiefly from public-sector corrections officers’ unions. The most active corrections officers’ union, the California Correctional Peace Officers Association, has contributed massively in support of “tough on crime” positions on voter initiatives and has given money to crime victims’ groups, and similar unions in other states have endorsed candidates for their tough on crime positions. Private firms would thus enter a heavily populated field and partly displace some of the existing actors.

Second, there’s little reason to believe that increasing privatization would increase the amount of self-interested pro-incarceration advocacy. In fact, it’s even possible that increasing privatization would reduce such advocacy. The intuition for this perhaps surprising result comes from the economic theory of public goods and collective action.

The political benefits that flow from prison providers’ pro-incarceration advocacy are a “public good,” because any prison provider’s advocacy, to the extent that it’s effective, helps every other prison provider. When individual actors capture less of the benefit of their expenditures on a public good, they spend less on that good; and the “smaller” actors, who benefit less from the public good, free ride off the expenditures of the “largest” actor.

Today, the largest actor—the actor that profits the most from the system—tends to be the public-sector union, because the public sector provides the lion’s share of prison services, and public-sector corrections officers benefit from wages significantly higher than those of their private-sector counterparts. The smaller actor is the private prison industry, which not only has a smaller proportion of the industry but also doesn’t make particularly high profits.

By breaking up the government’s monopoly of prison provision and awarding part of the industry to private firms, therefore, privatization can reduce the industry’s advocacy by introducing a collective action problem. The public-sector unions will spend less because under privatization they experience less of the benefit of their advocacy, while the private firms will tend to free ride off the public sector’s advocacy. This collective action problem is fortunate for the critics of pro-incarceration advocacy—a happy, usually unintended side effect of privatization.

This is the simplest form of the story, but one can also tell more complicated versions in which privatization doesn’t necessarily decrease total industry-expanding political advocacy. After presenting my main model, I introduce some realistic complications. Some of them don’t change the basic result of the model; others make the effect of privatization ambiguous—increasing private-sector advocacy but also decreasing public-sector advocacy. Either way, we don’t unambiguously predict that privatization increases advocacy. There is thus no reason to believe an argument against prison privatization based on the possibility of self-interested pro-incarceration advocacy—unless the argument takes a position on how lobbying, political contributions, and advocacy work, and why any increase in private-sector advocacy would outweigh the decrease in public-sector advocacy. Either this argument against prison privatization is clearly false, or it’s only true under certain conditions that the critics of privatization haven’t shown exist.

Consider the main political actors in the prison industry: the private prison firms and the public corrections officers’ union. I only focus on these two actors here because the other potential prison-based actors—private-sector employees and departments of corrections—don’t participate in pro-incarceration advocacy. Private-sector workers aren’t unionized, which makes it hard for them to act collectively (Shichor 1995; Dolovich 2005), and public departments of corrections actually want fewer prisoners (Woodford 2006; Allen 2006; Huppke 2006). I also assume that the private sector acts as a bloc (instead of competitively, and instead of, at the opposite extreme, cooperating with the public sector in a grand prison coalition) because cooperation within a concentrated oligopoly isn’t that difficult. Firms interact with each other a lot and have ample opportunity to punish each other for non-cooperative behavior (Ayres 1987). Moreover, private-sector firms interact with each other more than they do with the public sector, so enforcing cooperation across the whole prison industry would be harder than merely doing so among private firms. (However, it turns out that how the industry cooperates, or whether it cooperates at all, doesn’t make much of a difference for the main result.)

Without privatization, the public sector is the monopoly provider of prison services, and the corrections officers’ union enjoys the benefits that flow from serving the whole system. As explained in the general model earlier, as part of the system is privatized, the public sector’s advocacy decreases, while the private sector free rides off the public sector. This will remain true provided the public sector stays the dominant sector. And at current levels of privatization, the public sector is indeed dominant. It has a larger industry share and extracts more benefit from the system than does the private sector.

We can perform some rough estimates to verify this. (I assume, following much of the economic literature on firms and unions, that firms maximize profits, and that unions maximize total “union rents”—that is, here, the difference between public sector and private sector wages times the size of the public sector. See Farber 1986.)

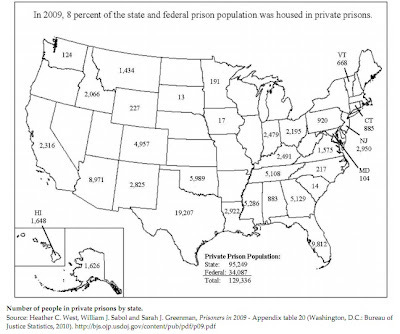

Industry share: The private sector has a smaller share of the industry. Of the 1.5 million prisoners under the jurisdiction of federal or state adult correctional authorities in 2004, 7 percent were held in private facilities (14 percent of federal prisoners and 6 percent of state prisoners). Among the 34 states with some privatization, the median percentage of private prisoners was 8 to 9 percent. If we’re interested in the private share of marginal prisoners—that is, how likely a prisoner is to go to a private prison if convicted today—the private share becomes larger, mainly because private firms have absorbed much of the recent growth in federal incarceration. A reasonable estimate of the private share of marginal prisoners over the period 2000–2005 yields 6 percent for state systems, 54 percent for the federal system, and 22 percent overall (U.S. Department of Justice 2004; U.S. Department of Justice 2005).

Private sector profitability: The profits of the private sector aren’t high; 10 percent would be a generous estimate (Volokh 2007).

Public sector rents: Public-sector correctional officers’ wages are quite a bit above—by about 30 to 65 percent—the wages of their private-sector counterparts (Criminal Justice Institute 2000a, 2000b). This is a lot of money, because wages are about 60 to 80 percent of most prisons’ operating expenses (Donahue 1989; Dolovich 2005; Logan 1990; Schlosser 1998; Shichor 1995).

The theoretical model and rough numerical estimates predict that pro-incarceration advocacy should come from the public sector, not the private. Are such simple, highly stylized models realistic? In the case of prisons, the simple model may be close to true. As I document later, there’s a lot of hard evidence of pro-incarceration advocacy by public corrections officers’ unions (though a small part of union advocacy cuts the other way). But there’s virtually no evidence of private-sector pro-incarceration advocacy. This may simply mean that the private sector advocates incarceration secretly. But, in light of the theory, it may be more plausible that the private sector simply is a free rider, saving its political advocacy for policy areas where the public good aspect is less severe—pro-privatization advocacy.

But this model doesn’t need to be literally realistic. Advocacy needn’t be an entirely public good, and the smaller actors in the industry needn’t be complete free riders. The point is merely that these assumptions are plausible, perhaps even likely. Advocacy has some public-good aspects, and free riding happens to some extent in the world. If people act enough like this model, privatization can still, on balance, reduce total pro-incarceration advocacy.

This plausible scenario rebuts the simple anti-privatization claim that privatization does increase pro-incarceration advocacy. (The extended models presented later on, in which the effect of privatization on advocacy is ambiguous, further rebut the simple unidirectional claim.) This scenario also points out a potential irony in the position of some incarceration opponents who, so as to avoid “reinforc[ing] the incarceration boom by introducing the profit motive into incarceration” (Sarabi and Bender 2000), would make common cause with public corrections officers’ unions, who concededly are active lobbyists for incarceration.

http://www.volokh.com/2013/01/10/the-effect-of-privatization-on-the-public-and-private-prison-lobbies/

The effect of privatization on the public and private prison lobbies - part 2.

http://www.volokh.com/2013/01/11/the-effect-of-privatization-on-the-public-and-private-prison-lobbies-part-2/

The effect of privatization on the public and private prison lobbies - part 3.

http://www.volokh.com/2013/01/14/the-effect-of-privatization-on-the-public-and-private-prison-lobbies-part-3/