The Police Executive Research Forum reported 71 percent of America's police agencies are using automatic license plate readers.

St. Louis - A shooting in July near the downtown riverfront followed a common pattern: The gunman disappeared before police arrived. Witnesses said he fled in a white Saturn, and they remembered only part of the license number.

But the suspect was caught in a rather uncommon way: using one of law enforcement’s newest — and potentially controversial — technologies.

St. Louis police detectives punched the witness information into a computer and learned that such a car had been spotted in the past at a nearby apartment complex. Then they used surveillance video at businesses in between to trace the car’s path to and from the shooting scene. The attacker was identified and in an interview admitted the shooting, claiming self-defense.

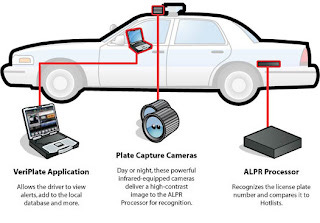

It turned out that a photo of the car and its license plate number were among 3 million scanned at random by cameras atop six city police cars equipped with an automatic license plate recognition system, said Detective Andrew Griffin, who has made extensive use of it. Times and locations are logged and saved with the images.

Officer William Belcher of the St. Louis County police said his department’s cameras have resulted in hundreds of arrests and “lots of guns and drugs” being found.

The success story is echoed around the country. Studies show that police who use such systems, commonly called automatic license plate readers (ALPR), report increases in productivity, arrests and recoveries of stolen vehicles.

The cameras, which may be barely noticeable nestled among patrol cars’ rooftop warning lights, can log thousands of images an hour. Nationally, agencies are adding them and interconnecting the information. In the Cincinnati area, data are linked among 10 counties in three states.

But critics worry about potential mischief with so much information collected on ordinary people’s movements.

“Our concern is that ALPR (systems) are used to collect and store info, not just of people suspected of crimes, but of every single motorist,” said Anthony Rothert, legal director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Eastern Missouri. “And they’re increasingly becoming a tool for routine tracking and surveillance.”

Rothert said ACLU affiliates around the country surveyed a limited number of police agencies this year, seeking information about their use of the technology. The ACLU plans to use open records laws to learn more about how the data are collected, stored and used. He said the organization also is “looking at possible legislation to balance legitimate law enforcement purposes ... with privacy.”

“There are legitimate reasons that law enforcement can use this technology,” he said. “There’s just a lot of potential for ... forcing us to surrender information about ourselves that is private. Where we go to church. What political events we attend ... what doctors we go to.”

It is difficult to determine how many of the dozens of St. Louis-area police departments use the cameras. Officers in St. Louis, St. Louis County, Chesterfield, Maplewood, Richmond Heights and Town and Country are among those who do. St. Louis has six. St. Louis County has three, with one assigned to the north, one to the south and one in Jennings, which the county patrols under a contract.

In a March 2011 survey by the Police Executive Research Forum, a nonprofit group that studies law enforcement issues, 71 percent of the agencies that responded were using plate readers. In the next five years, even more expect to get them, and some agencies think they will have as many as 25 percent of their vehicles equipped.

The group’s January report, “Critical Issues in Policing,” describes a study in Mesa, Ariz., that found officers with camera-equipped cars made twice as many arrests and recovered twice as many stolen cars.

St. Louis keeps its records for one year, based on a poll of other departments, Kreynest said. One million of the 3 million license plate records the department has read have already been purged.

Minneapolis Assistant Chief Janeé Harteau: "We situated our LPRs on bridges to capture as much data as possible. We’re just beginning to use license plate recognition now. Currently we have about six mobile devices and one permanent, which is not as many as we’d like. We’ve placed the ones we have on heavily trafficked bridges."

Sacramento Chief Rick Braziel: "A shopping mall does LPR scanning of their parking lots.

We use LPRs in our department, and a local shopping mall uses license plate readers in their parking lots. In 27 months, they were able to capture about 3 million plates. Auto thefts decreased by 66 percent at the mall, and through this program we’ve identified homicide witnesses and robbery suspects. As of a couple weeks ago, they had identified 51 stolen

vehicles in the parking lots, and we were able to getabout 41 arrests out of that.

When the mall employees get a hit, they call us.They keep the data for 30 days. Our detectives also can do a quick query when there are crimes in or around the mall area and it might be useful to know whether a certain car was at the mall at a certain time."

The International Association of Chiefs of Police sees a distinction separating vehicle information from personally identifiable information, such as names, dates of birth or fingerprints. The vehicle data are collected in public areas with no expectation of privacy, the group says.

Griffin, with the St. Louis police, said using the license plate readers is like photographing cars on a public street, with little chance of being able to recognize anyone inside. “I don’t recollect ever seeing a clear shot of the interior of the automobile via LPR,” he said.

Rothert, of the ACLU, said that only two states, Maine and New Hampshire, currently limit the use of such data.

Rothert said it is a core American principle that government does not collect information on people “just in case they do something wrong. We only collect information about citizens when we suspect wrongdoing.”

“I think that there need to be ... clear regulations to keep authorities from tracking our movements on a massive scale,” he said. “The technology and the local police departments are getting ahead ... of the law in protecting our privacy.”

http://www.stltoday.com/news/local/crime-and-courts/police-cameras-gobbling-up-driver-data-in-st-louis/article_69e3fb59-9fb2-5757-a5b6-820827eec7a3.html

ELSAG North America:

ELSAG North America is the developer of the Mobile Plate Hunter-900®, the most accurate, most deployed Automatic License Plate Reader available. It is deployed in over 570 agencies across all 50 U.S. states, aiding in missions such as recovery of stolen vehicles, highway safety, collection of delinquent taxes, drug interdiction, homeland security and many more. The MPH-900 has proven itself an invaluable law enforcement tool. It reads up to 50 plates a second from all 50 states, day or night, in any weather.866.9MPH900.

E-mail: luci.sheehan@elsagna.com

www.elsagnorthamerica.com